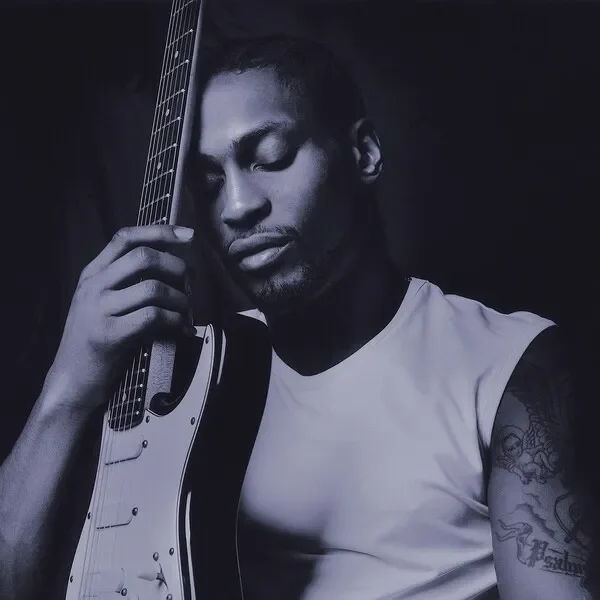

The Thing About D'Angelo: D’Angelo’s Impact on Black Music

D’Angelo showed the world that Black art could be raw, revolutionary, and real, reminding us that true soul doesn’t follow trends but transforms them! We discuss it here!

By: Jamila Gomez

When people talk about D’Angelo, they often start with the music. But to understand what he meant to Black culture, you have to go beyond sound. D’Angelo wasn’t just a musician. He was a mirror, a prophet, and sometimes a warning. He represented what happens when a Black artist refuses to shrink or simplify himself to fit what the world expects.

In the mid-90s, R&B had become shiny and predictable. The soul was still there, but it was buried under polish and performance. Then D’Angelo came along with Brown Sugar and reminded us that groove and grit could coexist. He made music that felt human again. He brought back live instruments, imperfections, the subtle hum of something real. He reconnected a generation of listeners to the lineage of Marvin, Stevie, Curtis, and Prince—but he didn’t imitate them. He carried their torch forward into a new era where hip-hop and soul could share the same body.

D’Angelo didn’t just make songs; he made soundscapes that told the truth about the interior life of Black people. That truth was layered—sensual and spiritual, sacred and messy. His second album, Voodoo, didn’t ask to be understood on first listen. It asked you to feel. It was swampy, slow, deliberate, drenched in history and pain and pleasure. And it came from the Soulquarians, a creative collective that refused to fit into industry molds. That was part of his power: he didn’t just make music that sounded different; he lived differently. He stood for experimentation, for artistry over commerce, for soul over spectacle.

But spectacle still found him. The video for “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” turned him into an icon, but not on his own terms. What was meant to be intimate became a cage. The world fell in love with his body before they finished listening to his voice. That moment revealed something deeper about how America treats Black men: celebrated when desirable, dehumanized when complex. The burden of being a symbol was heavy, and it broke him for a while. His retreat from fame wasn’t weakness. It was survival.

When D’Angelo returned with Black Messiah after fourteen years, it wasn’t nostalgia—it was resurrection. The country was in turmoil. Black Lives Matter was rising. The air was thick with grief and resistance. And here he came, raw and raspy, singing like he’d been through something holy and hard. That album didn’t cater to playlists or radio. It sounded like a sermon from a weary preacher who still believes deliverance is possible. He reminded us that Black art doesn’t have to be clean to be sacred.

That’s what D’Angelo meant to Black culture: he gave permission to be fully human. To be brilliant and broken, sensual and spiritual, angry and tender. He made space for contradiction. He made silence feel powerful. In a world that tries to flatten Black artists into either saviors or sinners, he chose to be both—and neither. He lived inside the tension.

His absence was part of the message too. In his quiet years, we learned the value of retreat. That you don’t have to constantly perform your genius for it to be real. That disappearing can be a form of resistance. That healing can take as long as it needs to. His reemergence proved that creative integrity can outlast an industry that thrives on burnout and exploitation.

You can hear his fingerprints in the work of artists who came after him—Solange, Frank Ocean, H.E.R., Kendrick, even in younger singers who bend genre like it’s clay. But his influence isn’t only musical. It’s philosophical. He showed that Black artistry doesn’t need permission to evolve. That the soul isn’t something to be packaged—it’s something to be protected.

When we talk about D’Angelo now, we’re not just mourning a man. We’re acknowledging a blueprint. He taught us that beauty and rebellion are not opposites. That vulnerability is a form of strength. That Blackness, in all its shades and contradictions, deserves to be explored, not explained.

He reminded us that music can be a revolution without shouting. Sometimes the softest notes carry the most truth. Sometimes the quietest man in the room is the one changing everything.

D’Angelo meant to Black culture what the ancestors meant to him: continuity. A reminder that our art doesn’t have to fit the times—it can shape them. That the sound of freedom is never finished. It just keeps finding new ways to hum.